La na gCeapairi.

No, my fingers didn't get lost on the keyboard. This is Gaelic for "Day of the Buttered Bread."

(Or "Day of the Sandwich," depending on which translation tool I use. Any Gaelic-speaking reader out there who can set me straight?)

These days, the Irish celebrate New Year's just like most of us, I imagine – with bonfires and parties on New Year's Eve, a verse of Auld Lang Syne at midnight, and church on New Year's Day.

But 100 years ago and more, when hunger was always just one failed potato crop away, many Irish New Year traditions involved food. Like the rich barm brack (fruit cake) baked especially to be smashed against the door by the man of the house, to banish hunger from the land in the new year. (Luckily, the family was free to gather the pieces and eat them afterwards – apparently in Ireland there wasn't the bias against fruitcake there is here in America!)

In County Cork, crumbs were thrown out the windows and door to prove that no one inside was hungry. Similarly, many families placed buttered bread, or bread-and-butter sandwiches, outside the door on New Year's Day, again to show an absence of hunger. Thus, January 1 and its designation as La na gCeapairi: Day of the Buttered Bread.

Bread and butter might just be my ultimate comfort food. Perhaps it's the Irish in me - my grandfather came to America from Donegal, a county on the wild Irish northern coast.

But maybe it's simply that my mother's homemade white bread was a special treat. Our daily bread was Pepperidge Farm or Sunbeam; but occasionally Mom would break out the big mixing bowl, knead a batch of yeast dough, and bake a couple of plain white loaves. Simple as they were, their aroma, hot from the oven, drew us all into the kitchen, where we'd eat hot buttered bread – much as our Irish ancestors may have, hundreds of years before.

I'm celebrating New Year's this year with a loaf of Irish Raisin Bread. An amalgam of two cultures, Irish and American, it adds raisins and a touch of cinnamon to a simple white/wheat loaf. I figure fruit-stuffed barm brack gives me permission to use raisins, both golden and dark; and combining all-purpose flour with the usual Irish whole wheat lends the bread a celebratory air.

As we get ready to greet another year, let's not lose sight of our past, and the many wonderful cultural traditions we hold dear. Especially around bread, that most venerable of all foods. Bhliain nua sásta!

Let's get started - with a starter.

Why use a starter to make this bread? It's not sourdough, not particularly "artisan..."

We find that a simple overnight starter both enhances bread's taste AND its keeping qualities. The short amount of "extra" fermentation raises the bread's acidity level just enough that it stays fresher longer; and the organic acids and alcohol released during that fermentation add wonderful complexity to the loaf's flavor.

Place the following in a bowl:

1 cup (113g) King Arthur Golden Wheat Flour

1/2 cup (113g) cool water

1/8 teaspoon instant yeast

Can you use Irish-style wholemeal flour? Yes. What about regular whole wheat flour? Yes - preferably King Arthur!

Combine the flour, water, and yeast, mixing until all of the flour is moistened. Cover the bowl, and let the starter rest overnight (or for up to 20 hours or so), at room temperature; it doesn't need to be placed somewhere warm. It will expand and become a bit bubbly.

When the starter is ready, mix it with the following:

2 cups (241g) King Arthur Unbleached All-Purpose Flour

1 1/4 teaspoons salt

3 tablespoons (32g) potato flour or 1/3 cup (32g) dried potato flakes

3 tablespoons (50g) brown sugar, packed

1/2 teaspoon baking soda

2 1/4 teaspoons instant yeast

4 tablespoons (57g) butter, softened

1/2 cup (113g) lukewarm milk

Mix and knead to make a smooth, soft dough. The dough will seem dry at first, but as you knead it'll soften up.

Place the dough in a greased bowl or greased 8-cup measure, cover it, and let it rise for 60 to 90 minutes, until it's noticeably puffy though not necessarily doubled in bulk.

Gently deflate the dough. Knead in 1 cup (170g) golden raisins, dark raisins, or a combination; or currants. Your hands are the best tool here.

If you use currants instead of raisins, you'll have a greater distribution of fruit throughout the loaf, due to currants' smaller size.

How about if you simply increase the amount of regular raisins, for more fruit in each bite? We tried that, and found increasing the raisins slowed fermentation considerably, and also affected the bread's final rise, due to sugar leaching from the raisins into the dough. It made a nice loaf, for sure; but it was denser. If that's what you're after, double the raisins or currants to 2 cups, and bake in a 9" x 5" loaf pan.

Shape the dough into a log, and place it into a lightly greased 8 1/2" x 4 1/2" loaf pan. Cover the pan with a large overturned bowl, or tent it lightly with greased plastic wrap. Allow the dough to rise until it's crowned about 1/2" to 3/4" over the rim of the pan, 60 to 90 minutes.

Towards the end of the rising time, preheat the oven to 350°F.

Combine the following, and brush over the loaf:

1/4 teaspoon ground cinnamon

1 tablespoon (7g) confectioners' sugar

1 tablespoon (14g) cold water

Now, you can omit this cinnamon topping, if desired; it's not critical, but adds a nice hint of spice. The topping amounts as written make more than enough; we did it that way simply because it's easier to measure a tablespoon each confectioners' sugar and water than 1 1/2 teaspoons each. Drizzle the excess over your morning oatmeal!

Bake the bread for 20 minutes. Tent it loosely with aluminum foil, and bake for an additional 20 to 25 minutes, until it's golden brown and an instant-read thermometer inserted into the center registers at least 190°F.

Remove the bread from the oven, and turn it out of the pan onto a rack to cool.

Cool completely before slicing.

Wrap airtight, and store at room temperature for up to 5 days; for longer storage, wrap well and freeze.

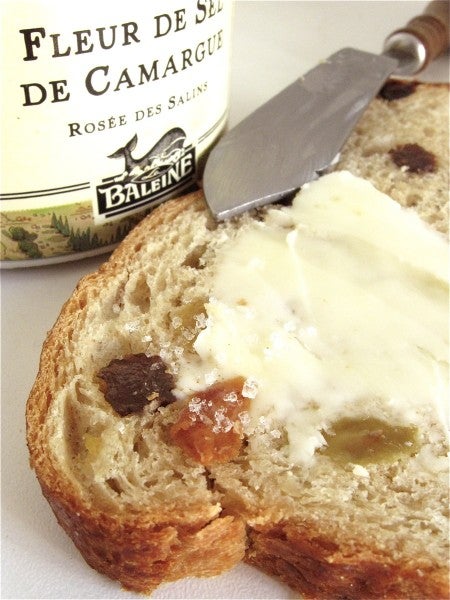

Here's a delicious, traditional way to serve this bread: with a smear of unsalted butter, and a sprinkle of sea salt.

Or simply spread with salted butter, and enjoy. The sweet raisins, rich butter, and touch of crunchy salt play wonderfully well together - my Irish eyes were definitely smiling as I enjoyed this New Year's treat!

Oh, and one more thing: if you find yourself with leftover bread starting to get stale - recycle it. Check out our post, Six ways to use up leftover bread.

Read, bake, and review (please) our recipe for Irish Raisin Bread.